Now, in mid-October, the London Royal Albert Hall — more accustomed to symphonies and state banquets — resounded with the thuds of 200-kilogram men

colliding. For five days, the hallowed concert hall hosted a full Grand Sumo Tournament, the first professional event of its kind outside Japan in more than three decades. Forty of the sport’s top wrestlers, or rikishi, entered the clay ring, or dohyō, in a spectacle that was equal parts athletic contest, spiritual ceremony and cultural diplomacy.

For Japan, the event was more than entertainment. It was a carefully crafted projection of soft power: a bid to export an emblem of national

identitywhile rejuvenating global interest in a sport facing ageing audiences and sporadic scandal at home. For Britain, it was novelty — a rare glimpse of one of Asia’s oldest living traditions, re-staged in the heart of London’s museum district.

Sumo is not easily transplanted. Every detail carries

ritualsignificance: the salt purifying the ring, the ceremonial stomps to chase away evil spirits, the silk aprons embroidered with ancestral symbols. To recreate this in London, organizers shipped tonnes of Japanese clay, rice straw and ceremonial gear. Even the gyōji — referees dressed like Shinto priests — were flown in to maintain authenticity.

The Royal Albert Hall, more used to string quartets than

yokozuna, required adjustments: reinforced flooring, wider seating, extra-sturdy chairs and, according to British tabloids, restrooms discreetly refitted to bear the weight of heavyweight visitors. The result was a curious but convincing fusion — an English Victorian landmark transformed into a Japanese shrine of strength.

The headline draw was Onosato Daiki, recently elevated to yokozuna rank, flanked by Mongolian veterans and a handful of European hopefuls. Each night, spectators watched bouts lasting seconds but rich in theatre: moments of feint, explosion and collapse, punctuated by applause and gasps from the velvet-seated crowd.

Tickets sold out within days. For the Japan Sumo Association, which organised the event, London’s success could pave the way for further international tours. The timing is deliberate: sumo, while still popular, has faced a run of

bad pressover bullying, hazing and match-fixing scandals. By showcasing discipline and grace abroad, the association hopes to remind the world — and perhaps its own fans — of sumo’s spiritual core.

The British audience, meanwhile, has proved a lucrative experiment. Corporate sponsors, Japanese airlines and whisky brands jostled for exposure. Merchandise — from salt pouches to plush wrestlers — sold briskly. If the economics add up, sumo may yet join the travelling circus of globalised sports, though the purists in Tokyo may wince at the thought.

There is a risk that, in translation, the essence of sumo is diluted. The chants and rituals that in Japan evoke quiet reverence may feel like

choreographyto Western eyes. Yet, as London’s spectators learned, the spectacle’s power lies in its contradictions — the combination of raw force and elaborate restraint, combat framed as ceremony.

Whether sumo’s London experiment endures is uncertain. But the sight of wrestlers bowing solemnly under the Hall’s great dome proved that, for now at least, the ancient art of Japan can still command silence — and awe — far from home.

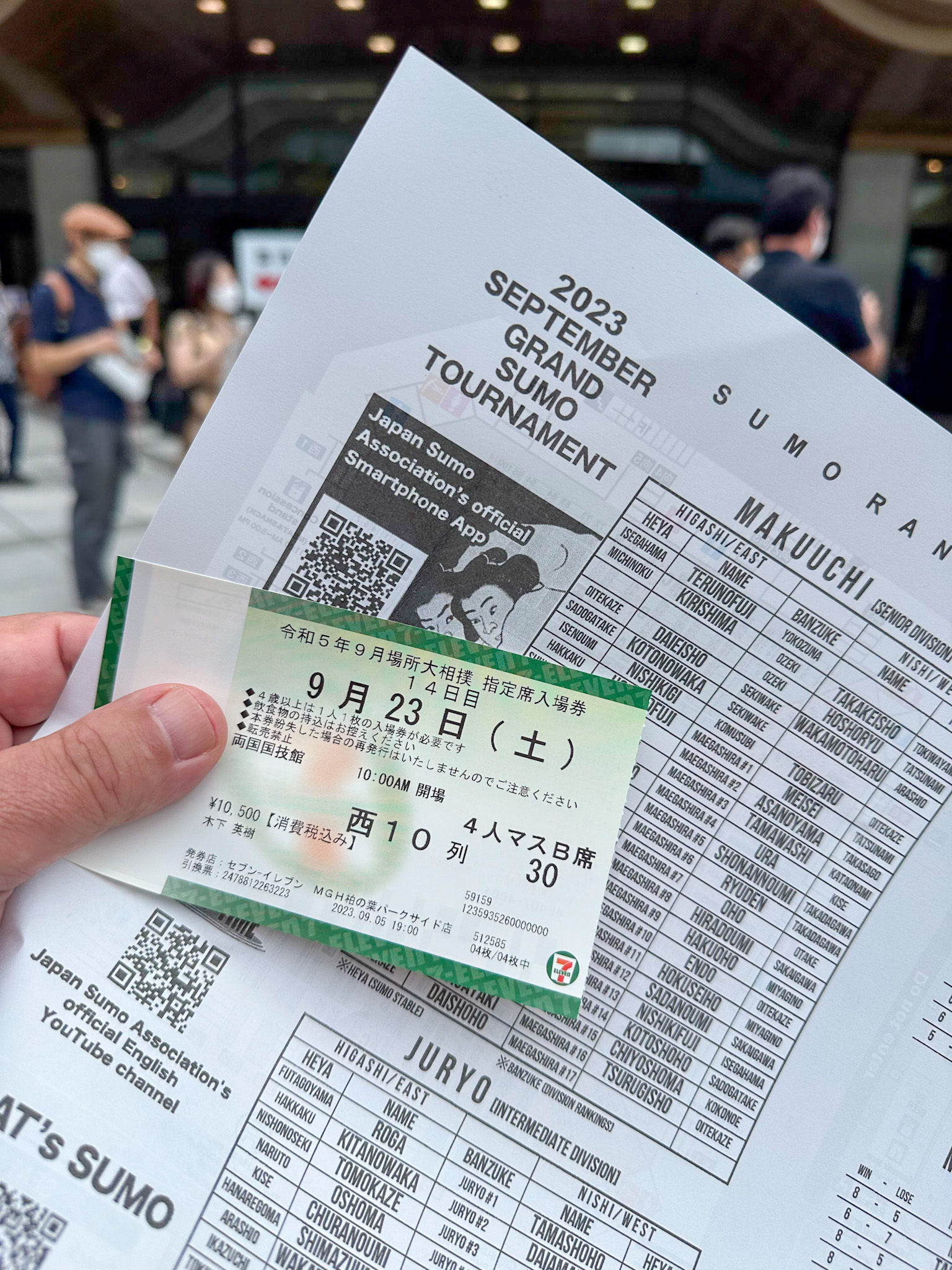

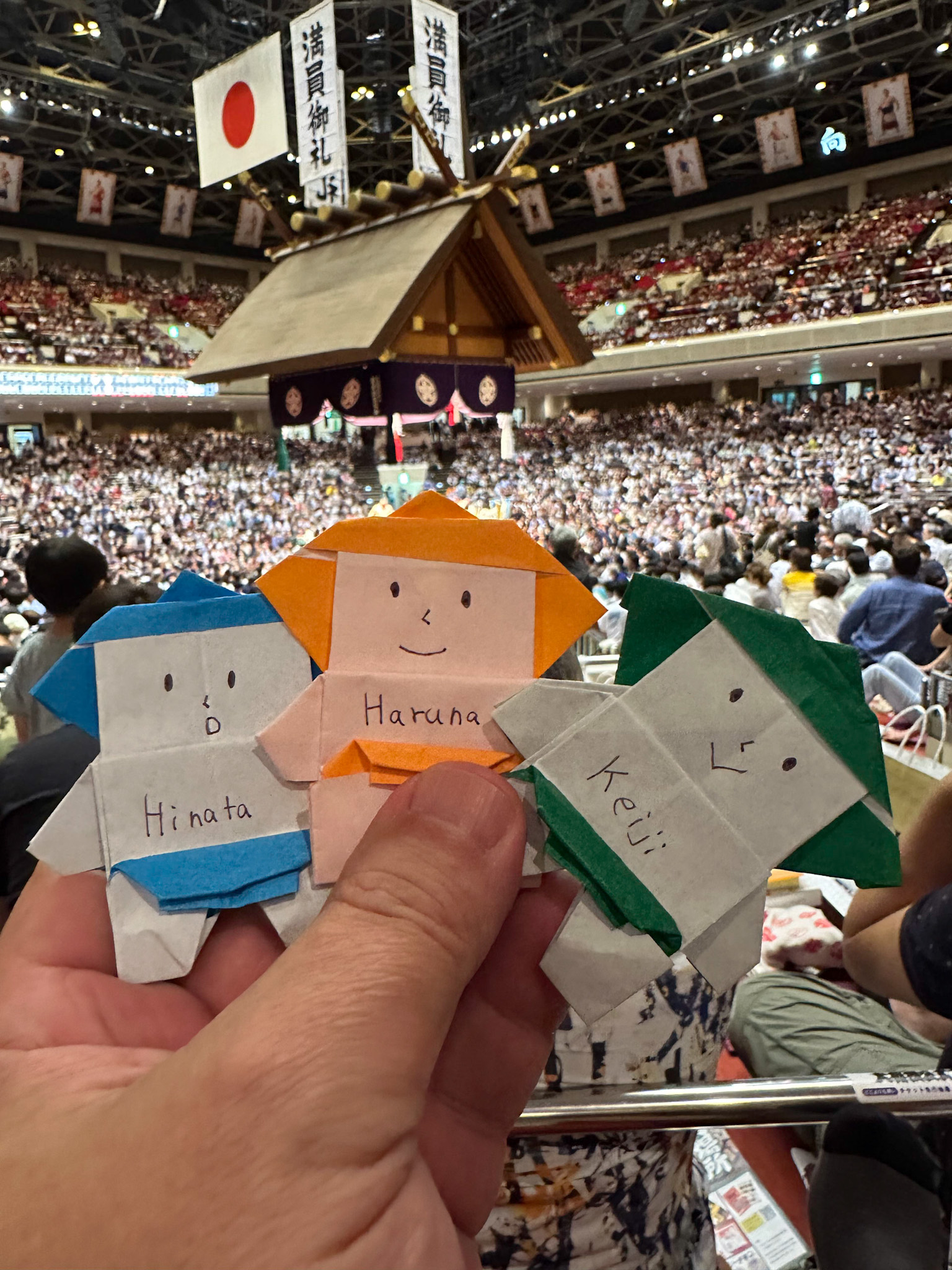

Photos: A couple of years ago, while spending six weeks traveling across Japan, I had the pleasure of being invited by some friends in Tokyo to attend a Grand Sumo Tournament. It was a moment I had been waiting for a long time — the chance to tick off one of my dreams. Seeing sumo live was nothing short of electrifying: the sheer power, ritual, and tension on the clay ring gave an unexpected thrill to a culture often defined by its calm and restraint.