There are policy decisions that arrive quietly, almost unnoticed, yet speak volumes about a country’s state of mind. China’s recent move to remove VAT

exemptionon contraceptives is one of them. On paper, it looks like a technical adjustment — a fiscal tweak meant to make products less affordable. In reality, it is a small window into a much larger unease: a nation grappling with the consequences of its own

demographic transformation.

For decades, China worried about having too many people. Now, it worries about

having too few— or, more precisely, too few young people, too few births, too many elderly, and a social contract under strain. The decision to intervene in something as intimate as contraception pricing is not about morality or ideology. It is about arithmetic. And arithmetic, in the end,

governs everythingfrom pensions to power.

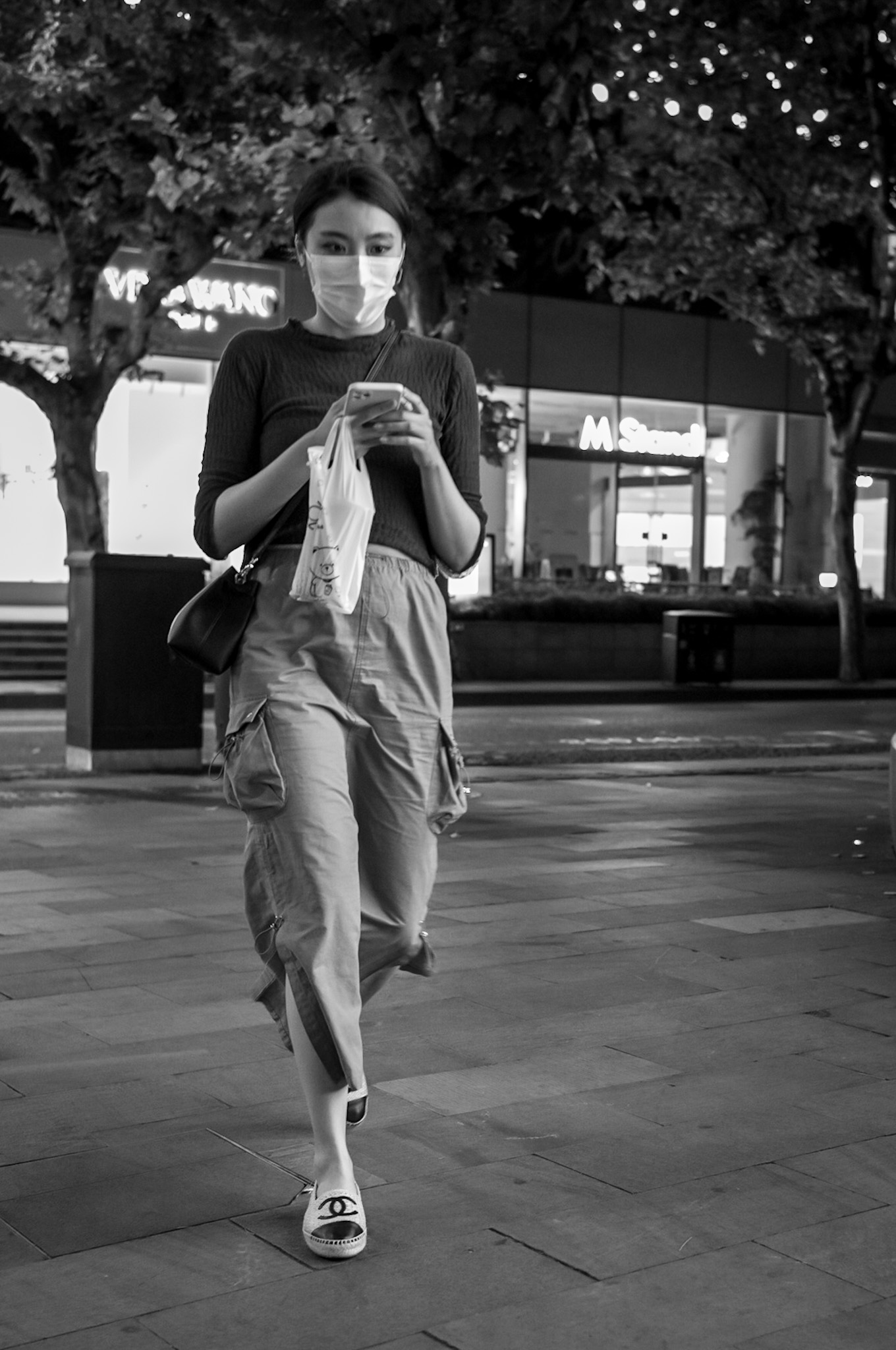

Walking through Chinese cities over the years — from the megacities of the coast to the quieter provincial towns — I have often been struck by the contrast between scale and

silence. Streets are busy, subways packed, shopping malls alive. And yet, playgrounds feel emptier than they once were. Schools

mergeinstead of expanding. Young couples move through life cautiously, calculating costs, careers, apartments, parents — and often deciding that one child, or none at all, is

the only manageable option.The VAT decision fits into this context. By increasing the cost of contraceptives, the state acknowledges a basic truth: family planning is no longer about

limiting births, but about managing choices. In a society where economic pressure, housing prices, work culture and childcare costs loom large, reproduction has become a carefully negotiated decision rather than an assumed stage of life. The government can encourage births through slogans and subsidies, but it cannot reverse decades of

structural changeovernight.

China’s shrinking population is no longer a projection; it is a lived

reality. Fewer newborns mean fewer future workers. Fewer workers mean slower growth, higher

dependencyratios, and rising pressure on

public finances. The famous “demographic dividend” that fueled China’s economic rise is fading, replaced by what economists politely call “

demographic headwinds.” For ordinary people, this translates into longer working lives, uncertainty about pensions, and a quiet anxiety about who will

carefor whom.

What makes this moment particularly complex is that demographic change is not just statistical — it is

emotional. Many young Chinese grew up as only children. They carry the weight of

supportingtwo parents and four grandparents, often while living far from their hometowns. Parenthood, once framed as

dutyor continuity, is now weighed against freedom, stability, and mental health. In this light, a tax policy on contraceptives becomes part of a broader

negotiationbetween state ambition and personal survival.

Long-term

planning, both individual and national, becomes harder in such an environment. Cities must rethink infrastructure designed for

perpetual growth. Companies must adjust to a smaller labor pool. Families must redefine what support networks look like in an

aging society. And policymakers must accept that reversing demographic decline is far more difficult than engineering it in the first place.

From the outside, China’s demographic dilemma is often discussed in abstract terms — charts, curves, projections. From the inside, it unfolds in kitchens,

nurseriesthat remain unused, and conversations postponed indefinitely. The VAT decision is a reminder that even the most technocratic systems ultimately intersect with

human lives, bodies, and choices.

Demography moves slowly, but its effects are relentless. China is now living inside the

long shadowof its past policies, trying to adapt without fully controlling the outcome. The question is no longer how to manage population growth, but how to live — thoughtfully and sustainably —

with less.

Photographs taken during my stays in 2024–2025 in Xintiandi, Shanghai’s pedestrian district near my office. In these frames, I am often drawn to people in motion, whose presence animates the urban landscape through style, gesture, and behavior.

Shot with a

LeicaM11 Monochrom and a

SonyRX1R II.