It is easy, with the comfort of distance, to think of ISIS as a chapter already

closed. A dark one, certainly—but finished. The images that shaped public memory are now a decade old: masked men, ancient ruins reduced to rubble, the declaration of a caliphate that seemed, for a brief and horrifying moment, to defy the international order. When the territorial structure

collapsed, many assumed the phenomenon had collapsed with it. That assumption was

wrong.

ISIS was never just a

placeon a map. Territory was a tool, not a definition. Once the tool became a liability, the organisation did what it had done before and would do again: it adapted. It’s a movement built on

mutation.

The roots of ISIS lie in the chaos that followed the

2003 invasion of Iraq, in a political vacuum where violence, sectarian fear and radicalisation fed off one another. What emerged from that environment was not initially a proto-state, but an insurgent logic: flexible, brutal, and opportunistic. Over time, that logic absorbed fighters, ideologues and survivors of other defeated groups, refining its methods and sharpening its narrative.

The declaration of a “

caliphate” in 2014 was the most visible phase of this evolution, but also its most fragile. Governing land brought revenue, legitimacy in the eyes of supporters, and an intoxicating sense of permanence. It also brought enemies, surveillance, and an unavoidable military response. When ISIS lost its cities, its checkpoints and its courts, it did not lose its capacity to kill—or to recruit. Instead, it

shed weight.

What followed was not disappearance, but

reversion: back to cells, couriers, intimidation, targeted assassinations and psychological warfare. Less spectacle, more

persistence. The kind of presence that rarely dominates headlines but steadily erodes security.

The Middle East

is no longer central, still relevant. In Iraq and Syria today, ISIS no longer governs openly. Yet it remains embedded in the margins: desert corridors, rural hinterlands, disputed security zones, and communities exhausted by years of

conflict and neglect. Attacks are smaller, less dramatic, but designed to remind both civilians and authorities that the organisation still exists.

Perhaps the most dangerous inheritance of the Middle Eastern phase is not military, but human: camps, prisons and displaced families holding thousands of people connected—

by blood or belief—to ISIS’s past. These spaces, suspended between punishment and reintegration, are fertile ground for radical continuity.

The caliphate is gone. The

ecosystemthat produced it is not.

If the Middle East is where ISIS learned to rule and then to lose,

Africais where it is now learning how to

endure, and where the centre of gravity have shifted.

Across the continent, ISIS-linked groups operate in environments defined by weak state presence, porous borders and populations caught between

insurgentsand heavy-handed security responses. What matters here is not ideology alone, but structure: the ability to insert violence into places where

authority is thinand trust in institutions already fragile.

West Africa, particularly the Lake Chad basin, has become one of the most active theatres. ISIS-aligned factions in Nigeria and neighbouring states have shown an ability to regroup, recruit locally and

sustain operationsdespite years of military pressure. In the

Sahel, similar dynamics unfold amid coups, international withdrawals and collapsing security arrangements. Elsewhere—such as parts of Mozambique—local grievances have been absorbed into a broader jihadist narrative, with devastating consequences for civilians.

This is not the rebirth of a caliphate. It is something more modest and, arguably, more resilient: a

network of franchisesthat borrow the ISIS name while operating according to local logics of power,

profitand

survival.

Let’s get now to the last few days, to the

U.S. strikein northern Nigeria—and the danger of simplification.

Against this backdrop, the recent U.S. airstrike against ISIS militants in northwest Nigeria should be read carefully. Conducted in coordination with Nigerian authorities, the operation reportedly targeted extremist fighters operating in Sokoto State, resulting in multiple militant deaths.

Militarily, such strikes can disrupt planning and remove experienced operatives. Politically, however,

the languageused to describe them matters almost as much as the munitions deployed.

Some public commentary framed the operation as a

defence of Christiansagainst religious persecution. Nigerian officials were quick to reject that framing—and rightly so.

ISIS-linked violence in Nigeria does not follow a single religious line. Christians are targeted.

Muslimsare targeted. Mosques and

churchesalike have been attacked. Civilians die not because of what they believe, but because they are reachable, undefended, and

trappedinside contested spaces.

Reducing this violence to a narrative of

Christians versus Muslimsrisks misunderstanding the conflict and, worse, reinforcing the very sectarian

divisionsextremist groups exploit. ISIS does not seek theological purity alone; it seeks

control through fear. Religion is a language it uses, not a boundary it respects.

What remains after the headlines fade: ISIS today is not a conquering army. It is a residue—persistent, adaptable, and

difficult to eradicate. Its presence in Africa is not proof of growing strength in the conventional sense, but evidence of strategic patience: an ability

to survive where governance failsand narratives simplify.

Airstrikes, arrests and military campaigns can contain the threat. They cannot, on their own, dissolve it. The longer struggle lies in

restoring trust, services and

legitimacyin regions where violence has become routine and life disposable.

To describe ISIS accurately in 2025 is to resist easy labels. It is not a

defeated ghost, nor a rising empire. It is a system of violence that has learned how to live without a capital city—and how to kill without asking

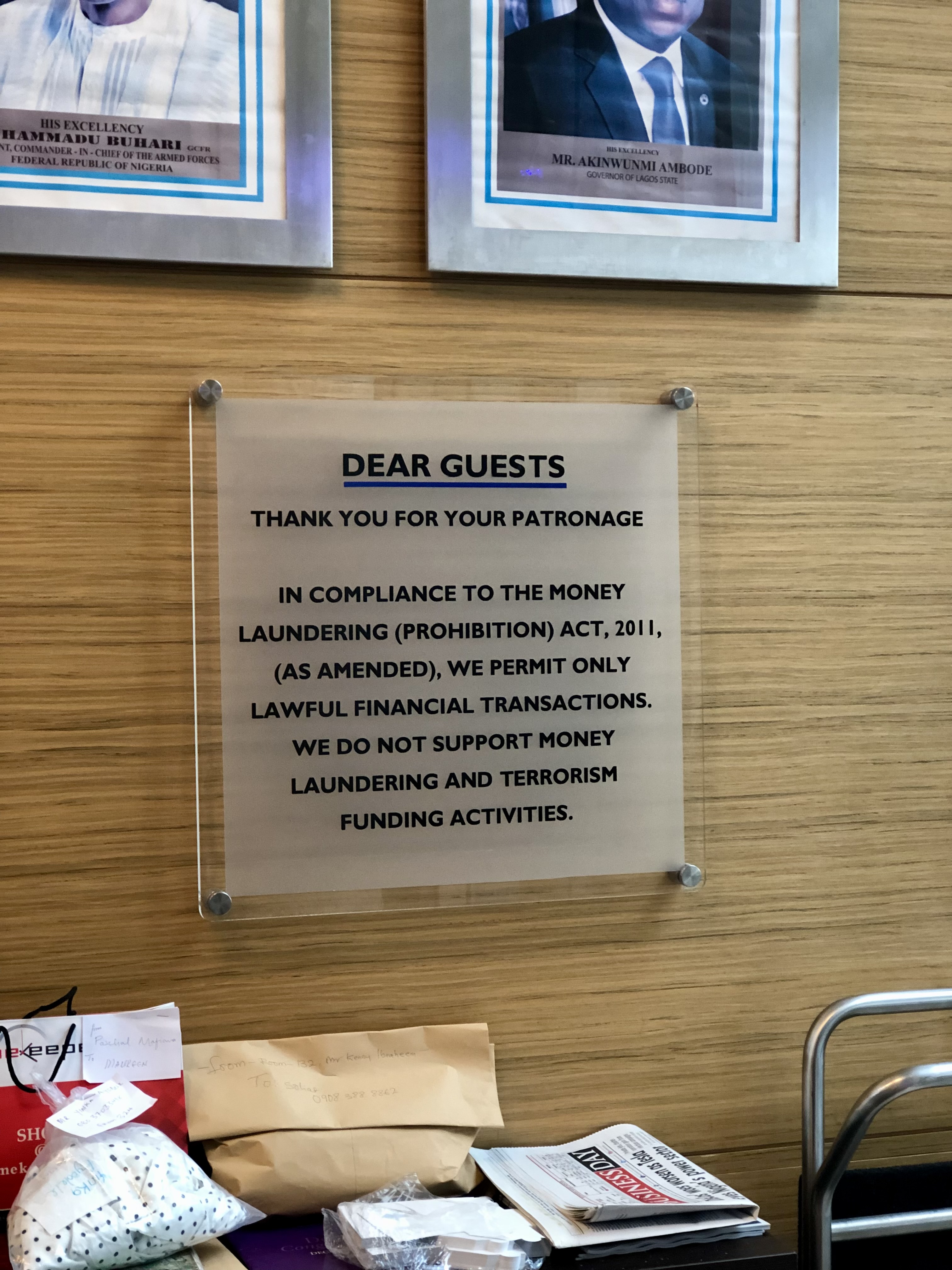

what its victims believe.I travelled to Nigeria many times between 2014 and 2020 to manage a series of highly complex operations, one of which I later recounted on my blog under the title Cuore di Tenebra.

Severe security constraints and confidentiality requirements consistently limited my ability to photograph freely. Still, while revisiting my archive, I came across a small number of images — most of them taken from inside the escort vehicle that was required to accompany me at all times, in a country where security remains a serious concern, even in its commercial capital, Lagos.