Back home, in the “Land of Sand Castles”, and from my window I can see a silver/grey dome, on the edge of Saadiyat Island. It’s the

Louvre Abu Dhabithat stands as a deliberate exercise in soft power. Opened in 2017 under a thirty-year agreement with France, the museum is both a cultural investment and a political statement: the Gulf’s most ambitious attempt to position itself as a global centre for art and knowledge.

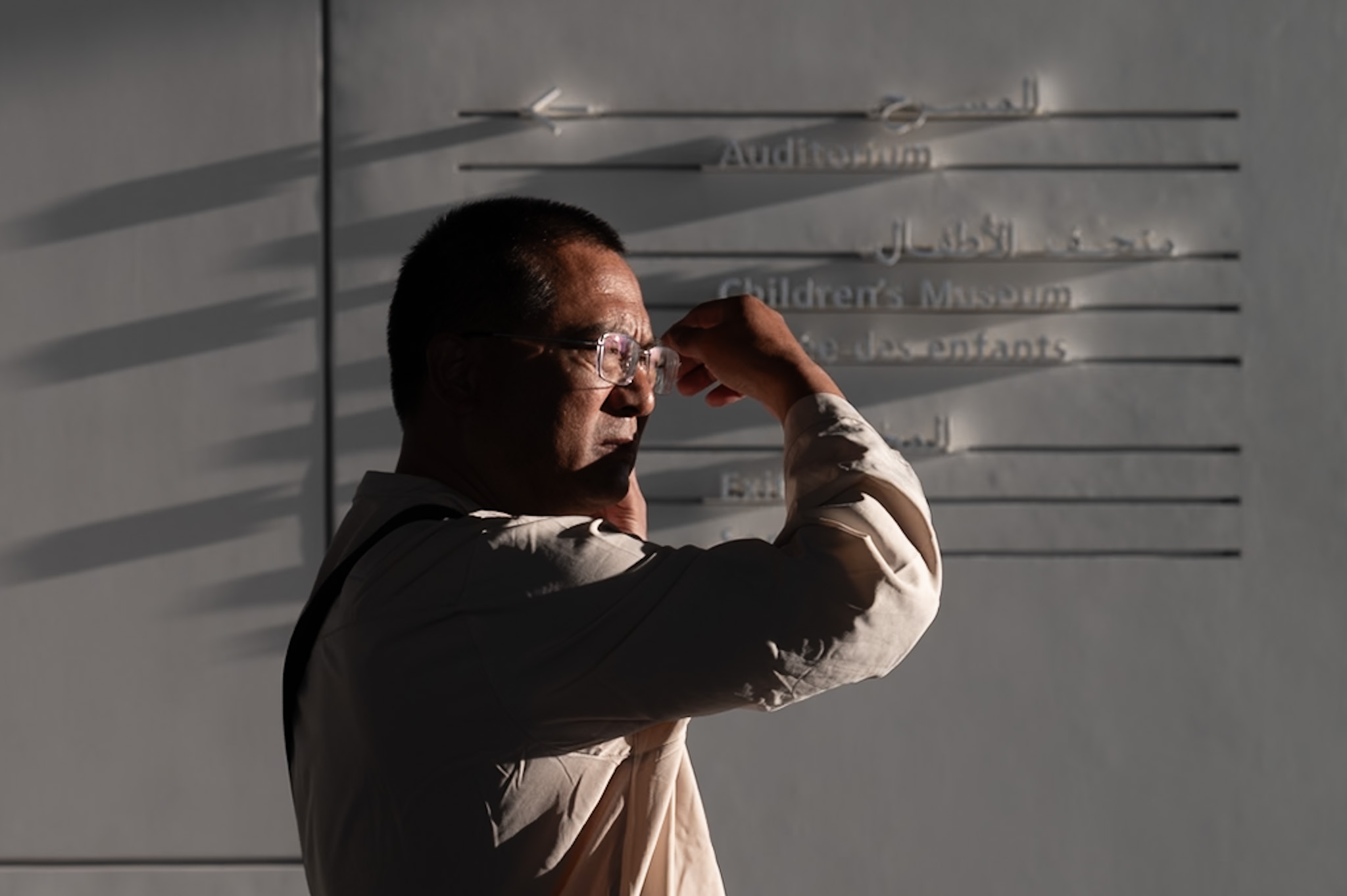

The building, designed by French architect Jean Nouvel, is striking but restrained. A vast steel dome — 180 metres wide and perforated with geometric openings — filters sunlight into a shifting pattern of light and shadow. The design is functional as much as symbolic, softening the desert glare while suggesting continuity with Islamic architectural traditions. The museum’s white walls and courtyards are cooled by air and water, turning a harsh environment into a contemplative one.

The visitor

experiencefollows a chronological and thematic route rather than a national one. Galleries are arranged around shared ideas — trade, belief, power, and representation — that link artefacts across cultures. A 3,000-year-old Egyptian sculpture may sit beside a Renaissance portrait or an African mask. This curatorial approach seeks to present world history as an

interconnectedstory rather than a succession of Western milestones. It is an idea borrowed from the Enlightenment but updated for a global age.

The collection itself is still developing. Around half the works on display come from French museums under a renewable loan system; others have been purchased directly by Abu Dhabi. Highlights include Leonardo da Vinci’s La Belle Ferronnière, works by Manet and Mondrian, and objects from Asia, Africa, and the Islamic world. The presentation is careful and uncluttered. Each gallery is designed to focus on a limited number of objects, encouraging

comparisonrather than accumulation.

Technology supports the experience without dominating it. Touchscreens, short films, and audio guides provide context. Multilingual signage is clear and

consistent. Families find dedicated learning spaces and a children’s museum. Visitor flow is well managed, though the transition between galleries and outdoor courtyards can feel abrupt in the summer heat.

The Louvre Abu Dhabi’s most distinctive quality is its tone. It avoids both academic density and national pride. The museum presents itself as

neutral territory— a place where different civilizations are treated with equal importance. This neutrality, however, is also its limitation. The narrative can feel cautious, avoiding the political and religious tensions that have shaped much of global art history.

For the Emirate, the project is part of a wider

economic diversificationstrategy. Culture, alongside tourism and education, is seen as a long-term alternative to hydrocarbons. The museum has drawn over four million visitors since opening, though attendance remains below pre-pandemic projections.

The overall impression is one of control and

balance. The Louvre Abu Dhabi is less a showcase of masterpieces than a carefully designed environment where architecture, curation, and

diplomacyintersect. Visitors leave with a sense of calm rather than revelation. The museum achieves what it set out to do: to offer a credible, international cultural experience in a region better known for its excess. In that, its restraint is its success.

I have a regular presence in the Louvre —almost every week—finding in it not only a haven for art, but also an inspiring space that nurtures (also with its free wifi) my work and writing. The photos are from my visits.