Last week I was sitting in my favorite pace in Singapore, Garibaldi, and while considering if there was some political affinity between the name of the restaurant and my

romantic-communistpolitical trust, the good friend sharing my dinner started asking “what’s next” after the GZ (Generation Z) raise in Indonesia, Nepal, Philippines and Morocco. “Maybe Malaysia is next?”, he added, challenging my view.

Now let me start with a disclosure: in 1927 my homonymous Mao (Tzedong) wrote "A revolution is not a dinner party, or writing an essay, or painting a picture, or doing embroidery; it cannot be so refined, so leisurely and gentle, so temperate, kind, courteous, restrained and magnanimous. A revolution is an insurrection, an act of violence by which one class overthrows another". I have to confess that, while sipping an amazing bottle of Barbaresco, tasting truffle on the scallops, and then cutting a Cotoletta alla Milanese, I was NOT the best guy entitled to talk about

RevolutionZ, but challenge was taken.

This is a quite detailed summary view on Malaysia.

Malaysia enters 2026 in a mood of uneasy pragmatism. The country has weathered a difficult year of public discontent, fiscal strain and fading patience with Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim’s reform agenda. Yet, beneath the noise of

street ralliesand subsidy debates, a quieter transformation is unfolding—one that may determine whether Malaysia escapes the middle-income trap or sinks deeper into it.

The unity government’s legitimacy has been dented by protests that drew thousands to Kuala Lumpur last July, accusing Anwar of back-pedalling on promises of transparency and economic renewal. Civil society groups lament that early enthusiasm for reform has given way to the familiar choreography of patronage politics. While the government remains stable for now, the coalition’s fragile balance of ethnic and ideological interests leaves little room for bold manoeuvres.

That constraint is proving costly. Malaysia’s

economy, while still one of Southeast Asia’s sturdier performers, is losing altitude. Growth in 2025 hovered around 4.4%, respectable but unspectacular in a region racing ahead. The central bank, Bank Negara Malaysia, cut its key rate to 2.75% last July—the first easing in five years—to nudge investment and domestic demand. Inflation remains benign at around 1.3%, thanks to generous subsidies. But those very subsidies, long a political crutch, now threaten to

hobblethe state’s finances.

Anwar’s government has promised to retarget assistance toward low-income households and scale back universal fuel subsidies. Yet each attempt to reform them sparks backlash. The public, squeezed by high living costs, is in

no mood for belt-tightening. The result is a half-measure: limited fiscal savings, persistent distortions, and creeping doubts about reform credibility. Oil and gas revenues, the traditional safety net, can no longer be counted on as global prices wobble. Petronas, the state energy giant, remains a cash cow but its dividends are not infinite.

Political unease complicates the picture. The opposition, anchored by the Islamist PAS, is regrouping in rural heartlands, while new political movements—such as the fledgling Parti Hati Rakyat Malaysia—seek to tap into youth frustration (GZ). Sabah’s forthcoming state election could test federal cohesion, especially if local parties push for greater autonomy and resource control. Malaysia’s politics, once predictable, are fragmenting.

Externally, the country faces headwinds. America’s new tariff regime has caught many of Malaysia’s exports in its net, with duties approaching 19% on selected goods. Global trade frictions and sluggish Chinese demand threaten the country’s manufacturing base, particularly in semiconductors and palm oil. FDI inflows have slowed markedly, falling in mid-2025 to their

weakestlevel in five years. Malaysia’s enviable logistics, rule of law, and English-speaking workforce no longer guarantee a steady inflow of investors as

competitionfrom Vietnam, Indonesia, and India intensifies.

Yet the story is not entirely bleak. The government’s forthcoming 13th Malaysia Plan (2026–2030) offers a

plausible blueprintfor renewal. It promises to modernize industrial policy, expand digital infrastructure, and promote green technology—all in an effort to lift productivity and build resilience. The plan’s success, however, hinges on execution, not design. Malaysia has long excelled at drafting visionary frameworks that falter in implementation.

Some early signs are encouraging. The

Johor–Singaporespecial economic zone, announced this year, could become a powerful magnet for investment and talent if bureaucracy is kept at bay. Plans for a rare-earths processing facility—reportedly under discussion with Chinese firms—may help Malaysia climb the resource value chain, provided environmental standards are upheld. The government’s push for targeted subsidies, combined with talk of a future carbon tax, signals at least a modest appetite for fiscal rationalization.

Opportunitiesalso abound in Malaysia’s pivot toward the digital and green economies. The 2026 budget earmarks funds for semiconductor expansion, renewable energy, and start-up incentives. Done right, this could position Malaysia as a regional hub for sustainable technology—a Southeast Asian bridge between manufacturing and innovation. The challenge will be to match investment with skills. Education reform, AI-driven training, and upskilling remain

slow. Unless Malaysia’s workforce adapts, the productivity gap with regional peers will widen.

adds urgency. The country’s population is ageing, while

youth unemployment (GZ, again)and regional inequality persist. Rural states such as Sabah and Sarawak lag far behind the urban peninsula, breeding resentment that risks morphing into populism. A credible social contract—balancing fiscal discipline with social protection—will be vital to preserving cohesion.

Beyond economics, Malaysia’s foreign policy remains deftly non-aligned. Anwar’s decision to invite U.S. president

Donald Trumpto the 2025 ASEAN summit drew bemusement abroad and criticism at home, yet it underscored Malaysia’s preference for pragmatic engagement over ideology. As geopolitical competition deepens, that balancing act may grow trickier: Malaysia must court China’s investment without alienating Western markets.

In sum, 2026 will test Malaysia’s capacity for

incremental reformunder duress. The country has the ingredients for resilience—political pluralism, fiscal institutions, and a diversified economy—but lacks the institutional stamina to sustain change once the headlines fade. The greatest risk lies not in crisis, but in

drift: a slow erosion of competitiveness, credibility, and public trust.

Still, the same forces that threaten Malaysia’s stability also create its opportunity. If the government can

phase outblanket subsidies, enforce governance reforms, and empower local industries to innovate, it could reclaim the narrative of a modern, inclusive nation. The alternative—a state mired in subsidies, populism, and missed potential—is all too familiar.

My view in a few words then? For Malaysia, 2026 is not a year of reckoning but of quiet choices. Whether those choices are bold enough will decide if the country merely copes—or truly moves forward.

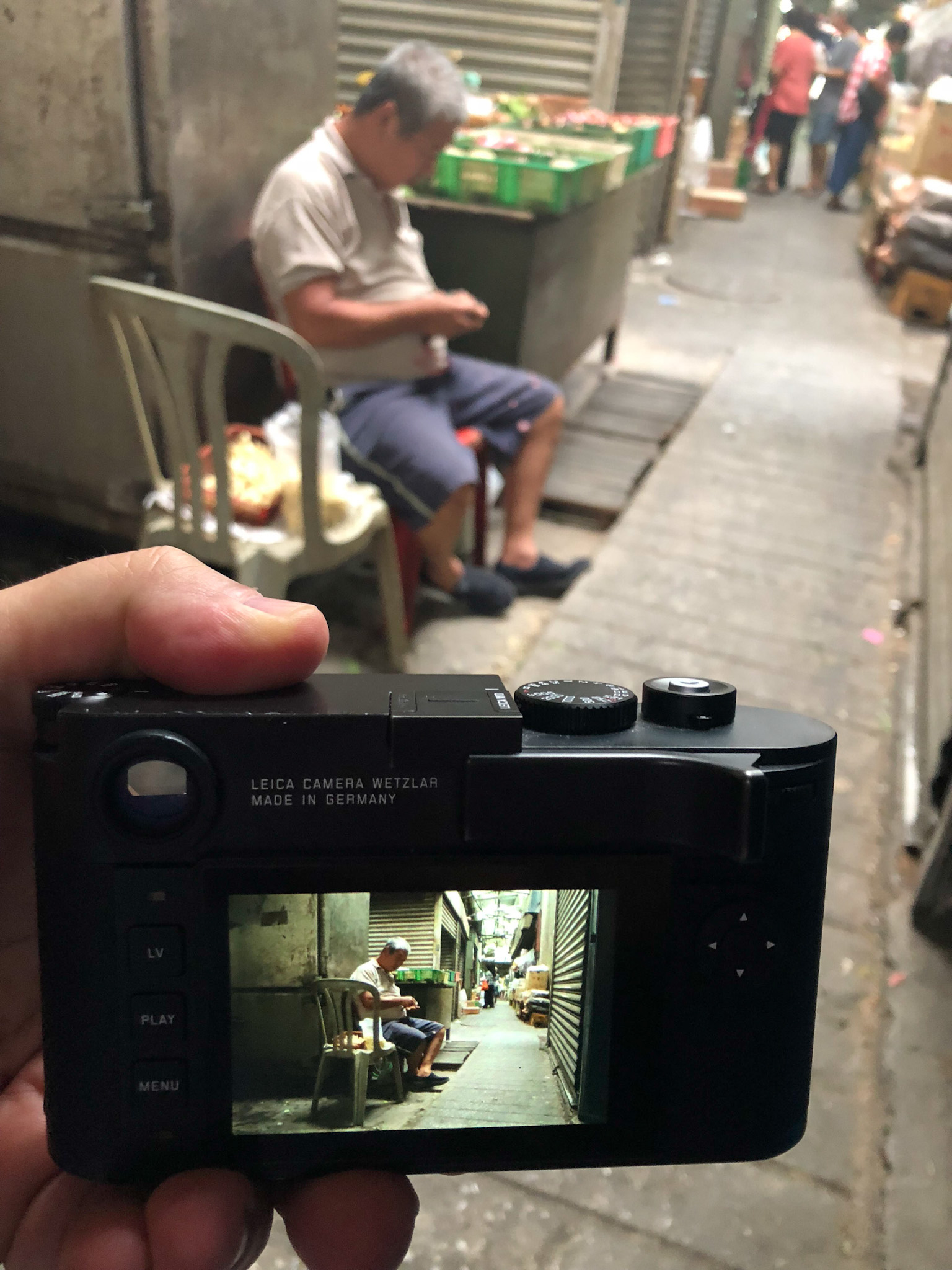

Photos: back in 2018 I spent a few days in Kuala Lumpur, taking the chance of a cancelled meeting to walk around the less-glamorous parts of city, far from downtown shopping bonanza. Yes, I was hand in hand with my Leica.