There is a moment, when you sit down in a restaurant somewhere in Asia, that you understand you are no longer the

protagonistof the meal. You are a guest — sometimes a welcome one, sometimes a tolerated one — inside a system that has its own rhythm, rules, and

quiet logic. Ordering food here is not a performance of personal taste. It is an act of negotiation with tradition, habit, and efficiency.

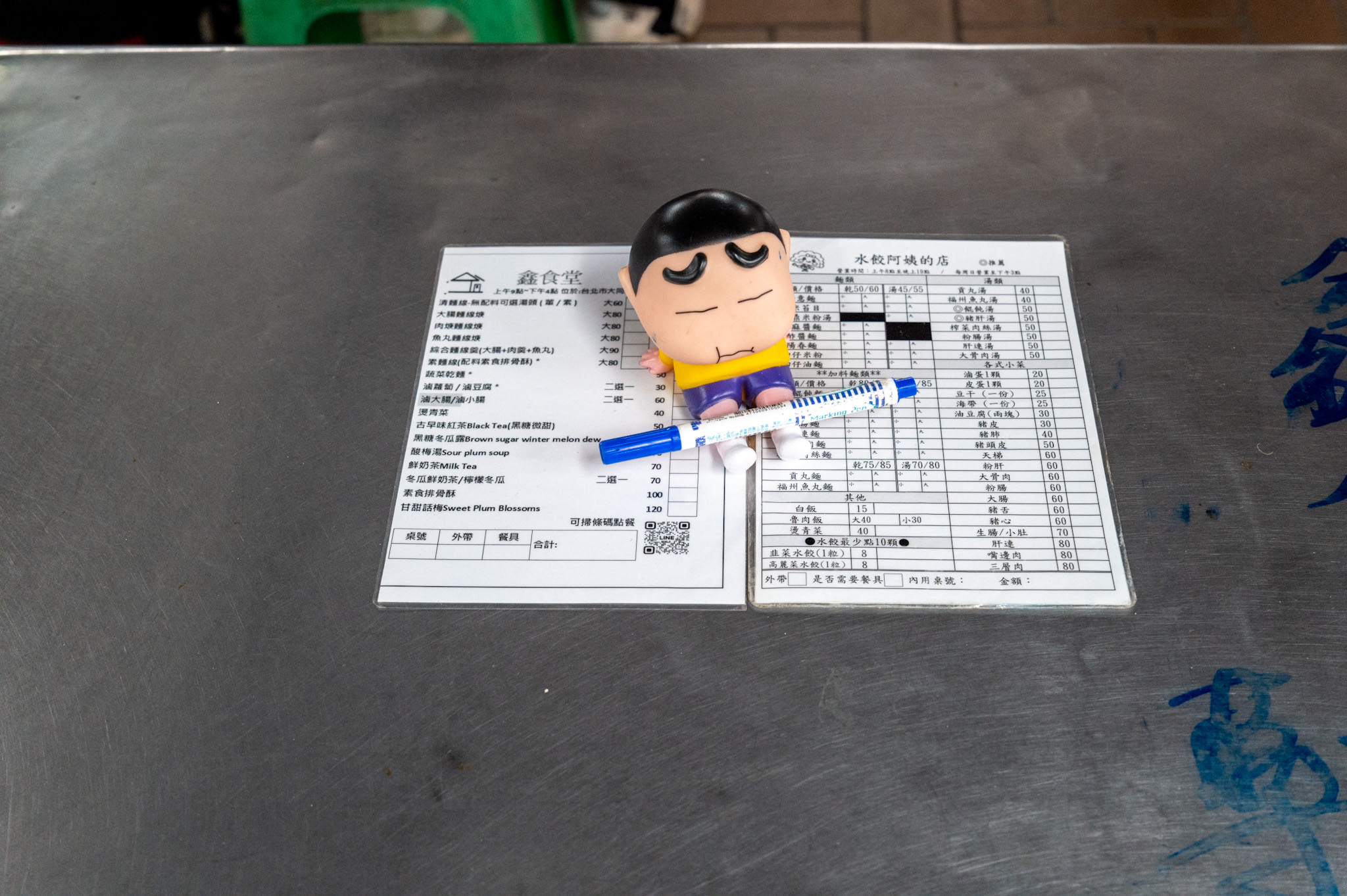

Menus are the first signal that you have entered a different grammar of

eating. In much of Asia, the menu is not designed to seduce you. It is designed to inform those who already know. Pages can be laminated, greasy at the edges, covered in dense blocks of text. Photos often replace descriptions, sometimes dozens of them, arranged without hierarchy. No storytelling. No adjectives. No reassurance. The dish

exists; it does not need to be explained.

In China, menus often feel encyclopedic. They assume familiarity. Ingredients are listed plainly, sometimes brutally. If you do not know what you are ordering, that is not the menu’s problem. In many places, the menu is a wall: large panels with pictures and

prices, visible from afar, optimized for speed and volume rather than intimacy. Pointing is not only accepted; it is encouraged. Language barriers dissolve through gestures and

finger taps. Precision comes second to flow.

Japan, on the other hand, offers a different form of clarity. Plastic food displays — perfect replicas of meals frozen behind glass — remove ambiguity entirely. You don’t read the menu; you

scan it visually, like an exhibition. This is food as object, food as promise. Even when written menus exist, they are often concise, focused, respectful of the dish’s identity. You are not invited to customize. You are invited to trust.

Across Southeast Asia, menus can be ephemeral. Chalkboards, handwritten sheets, printed A4 pages slipped into plastic covers. Sometimes there is no menu at all — just a few dishes

recited by memory, adjusted by availability and mood. What is being served today is what makes sense today. Ordering becomes a conversation rather than a transaction, even when language is limited to smiles and nods.

The

interactionwith waiters follows the same logic. In Asia, service is rarely performative. There is no ritualized friendliness, no scripted check-ins. Waiters do not hover. They do not ask if “everything is alright” every five minutes. Their role is functional, efficient, sometimes abrupt — and

deeply respectfulin its own way. They assume you are here to eat,

not to be entertained.

In many places, the waiter will not guide you through the menu unless you ask. And sometimes, even if you ask, guidance will be minimal. Recommendations may come in the form of a single gesture: a circle drawn on the menu, a nod toward a dish everyone else seems to be ordering. Popularity is a form of

validation. If many tables are eating the same thing, that is the recommendation.

There is also an unspoken hierarchy in ordering. Locals first, foreigners second. Regulars are recognized instantly. Their orders are taken without menus, without questions. You, instead, are given time — or ignored until you signal clearly that you are ready. This is not

rudeness. It is efficiency shaped by repetition. The restaurant exists to feed many, not to accommodate one.

Payment, too, reflects this mindset. Bills are direct. No itemized explanations, no theatrical presentation. Sometimes you pay at the counter, sometimes at the table, sometimes before you eat. Tipping is rare, often misunderstood. Gratitude is assumed to be expressed through return visits, not percentages.

What I have learned, over years of sitting at small tables under fluorescent lights or ceiling fans, is that ordering food in Asia requires a quiet

shiftof attitude. You stop trying to control the experience. You let go of customization, of special requests, of dietary performances. You accept that the dish has existed long before you arrived and will exist long after you leave.

When you embrace this, something changes. The meal becomes lighter. More attentive. You notice details you would otherwise miss: the speed of the kitchen, the choreography of plates moving across tables, the way a waiter remembers five orders without writing anything down. You understand that hospitality does not always look like warmth. Sometimes it looks like precision.

Eating in Asia teaches you that

respect can be silent, and that trust — in the menu, in the cook, in the system — is often rewarded. You may not get exactly what you expected. But more often than not,

you get exactly what you needed.

I have been traveling across Asia for more than fifty years, always immersing myself in local culture — starting with food — choosing experimentation and discovery over the comfort of familiarity.

The relationship with food and its intermediaries — cooks, waiters, and anyone else who places a bowl in front of you while you sit on a stool with a spoon in your hand — is one of the most fascinating social worlds one can enter and come to understand.

Photos from my last trip to Taipei, early December 2025.

Leica Q3 43.