In an era when words flicker across glass screens and

thumbsdictate more than hands ever wrote, one might assume the fountain pen to have gone the way of the telegraph. Yet, quietly and stubbornly, it persists—its nib glinting in conference rooms, classrooms and cafés. Sales of luxury writing instruments, after years of decline, are again on the rise. In Tokyo and Hamburg, in Milan and Chicago, a new generation of writers, designers and collectors has rediscovered the pleasure of

ink that flows, not clicks.

The fountain pen’s survival is a paradox of modernity. It thrives not despite, but because of, a digital world obsessed with speed and disposability. As emails multiply and messaging apps reduce communication to fragments, the

deliberateact of writing with a fountain pen feels almost rebellious. The slow rhythm of filling an ink converter, the scratch of nib on paper, the small pause before the next line—all remind the writer that words still have weight.

The economics of ink are curious. While the smartphone industry thrives on planned obsolescence, the fountain pen business relies on

permanence. A well-made pen may outlive its owner; its only consumable is ink, which costs a fraction of a printer cartridge. This durability gives it a peculiar allure in an age of waste. Yet, the sector’s real value lies not in units sold but in symbolism. The pen, in short, remains a totem of significance.

There is also a psychological dimension to its endurance. Handwriting activates parts of the brain linked to memory and creativity more effectively than typing. Photographers, designers and architects speak of how the smooth flow of ink fosters ideation.

Calligraphy, once a fading craft, has become a social-media niche: videos of nibs tracing copperplate flourishes draw millions of views. And in a post-pandemic world where mindfulness

sells, writing with a fountain pen has been rebranded as a form of analog meditation.

Still, the pen’s charm carries contradictions. Its elegance could often be elitist; a flagship Montblanc costs more than a mid-range smartphone, but you may still pick a Kaweco for a bargain. In China, domestic brands such as Hero or Wing Sung now export millions of pens yearly, catering to both students and global collectors—a rare instance of cultural nostalgia turned profitable export.

The fountain pen’s survival is thus not mere sentimentality. It is a quiet reminder that progress need not erase the past. As long as there are those who still prefer ink to pixels, handwriting to tapping, the pen will remain more than a relic—it will be a gesture of resistance, drawn in blue or black (or brown, like I prefer).

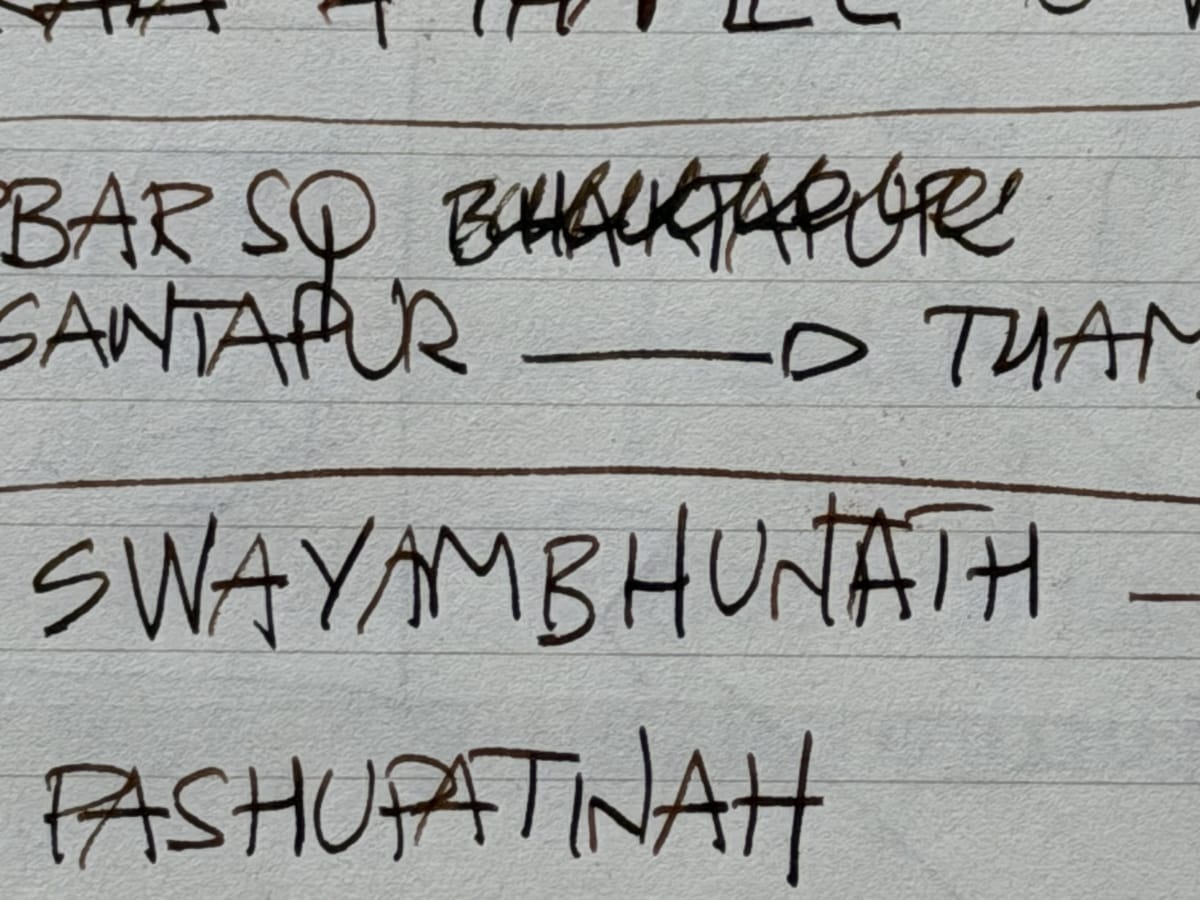

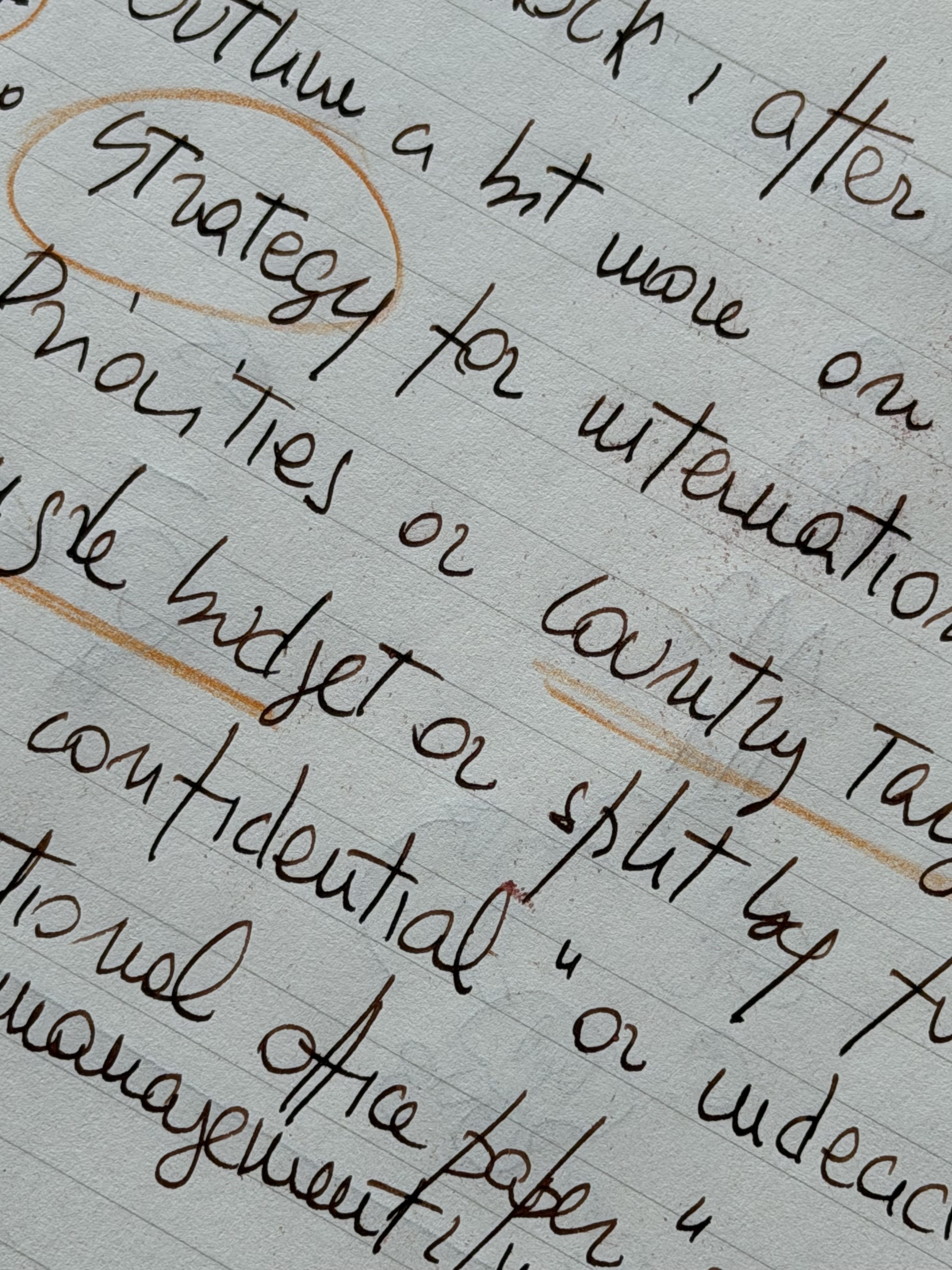

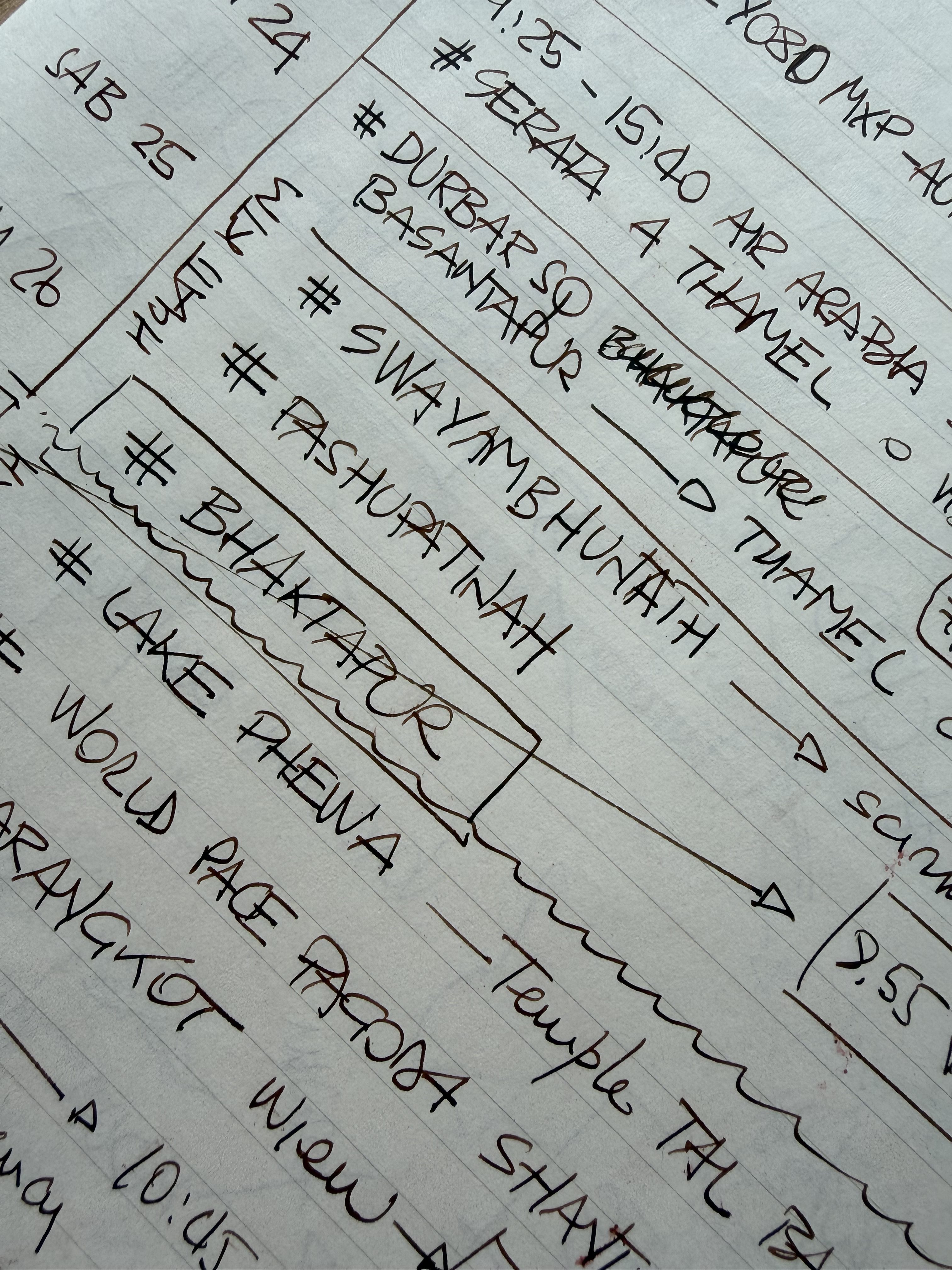

I’ve been using fountain pens all my life, even though I was an early — and rather enthusiastic — adopter of digital tools. Ink makes me think. It helps me design, sketch, and build mental maps that go far deeper into my senses than any brilliant piece of software ever could. It leaves space for mistakes, misspellings, language blends, and lines that will never be as straight as the pixels on a screen. The photos are from my most recent notes, written with my trusted nib, on Japanese paper.