At dawn, Sanur’s beach glows with pastel light as the first wooden jukungs, the island’s traditional outrigger boats, glide back to shore. Their

painted prowsslice the water like tropical birds, bringing home usually not abundance but modest catches—tuna, mackerel, or whatever the sea has spared that morning. For centuries, Bali’s fishing villages thrived on this rhythm of tide and trade. Today, that rhythm is faltering.

Indonesia, the world’s second-largest fish producer after China, owes much of its marine heritage to islands like Bali. Yet on this tourist-thronged paradise, the fishing industry sits uneasily beside five-star resorts, yoga studios, and digital nomads with MacBooks. Coastal communities such as Kedonganan, Serangan, and Kusamba still depend on the sea, but their prospects are clouded by overfishing, rising costs, and a shifting climate that plays havoc with once-predictable patterns of wind and current.

For the

small-scale fishermen—roughly 60% of Bali’s coastal workforce—the challenges are existential. Most operate tiny boats powered by second-hand engines, lacking refrigeration or sonar equipment. Trips must be short, and catches are perishable. Their income depends on the vagaries of the morning’s haul and the market’s mood by afternoon. The profits, after fuel and maintenance, are often meagre. Younger generations increasingly drift toward tourism, construction, or ride-hailing jobs, leaving the profession grey-haired and dwindling.

Environmental stress adds to the strain. The waters around Bali, once rich in pelagic fish, have been thinned by decades of unregulated trawling and illegal

foreign fleetsoperating just beyond detection. Coral reefs—crucial nurseries for marine life—have suffered from pollution,

dynamite fishing, and rising sea temperatures. Plastic waste chokes mangroves and drifts into nets. “We work harder for smaller fish,” says Made, a fisherman in Kusamba, shrugging as he repairs his torn gear. “The sea gives less every year.”

Local authorities and NGOs have launched initiatives to restore balance. Community-managed marine zones, known as perairan adat, are being revived under traditional Balinese law, awig-awig, to restrict destructive methods and protect spawning grounds. Fishermen’s

cooperativesare experimenting with seaweed farming and small-scale aquaculture to diversify incomes. Some coastal villages now sell “eco-fishing tours” to visitors seeking an alternative to beach clubs—an attempt to blend tourism’s cash with heritage preservation.

But such efforts face structural limits. Indonesia’s maritime policy, ambitious on paper, remains poorly enforced in

practice. Subsidies often favour industrial trawlers over artisanal fleets. The global appetite for tuna and reef fish continues to drive demand that small fishermen cannot meet sustainably. And as Bali’s coastline urbanises, traditional fishing settlements are squeezed between luxury developments and eroding beaches.

Yet

resiliencepersists. In Amed, on the island’s north-east coast, fishermen still venture out before dawn, guided by stars and instinct rather than GPS. They mend their nets communally and sell their catch at local markets where the currency of trust remains stronger than digital payments. Their lives are precarious but dignified—anchored in an ancient

intimacywith the sea that resists commodification.

Bali’s fishermen stand as reminders that paradise is not only a postcard but a place of toil. Their struggle mirrors a global paradox: as economies modernise and coastlines

gentrify, those who have lived longest with the ocean find themselves cast adrift. Whether tradition and modernity can share these shores will determine not only the fate of Bali’s fishing villages but also the moral depth of its much-advertised harmony with nature.

⸻

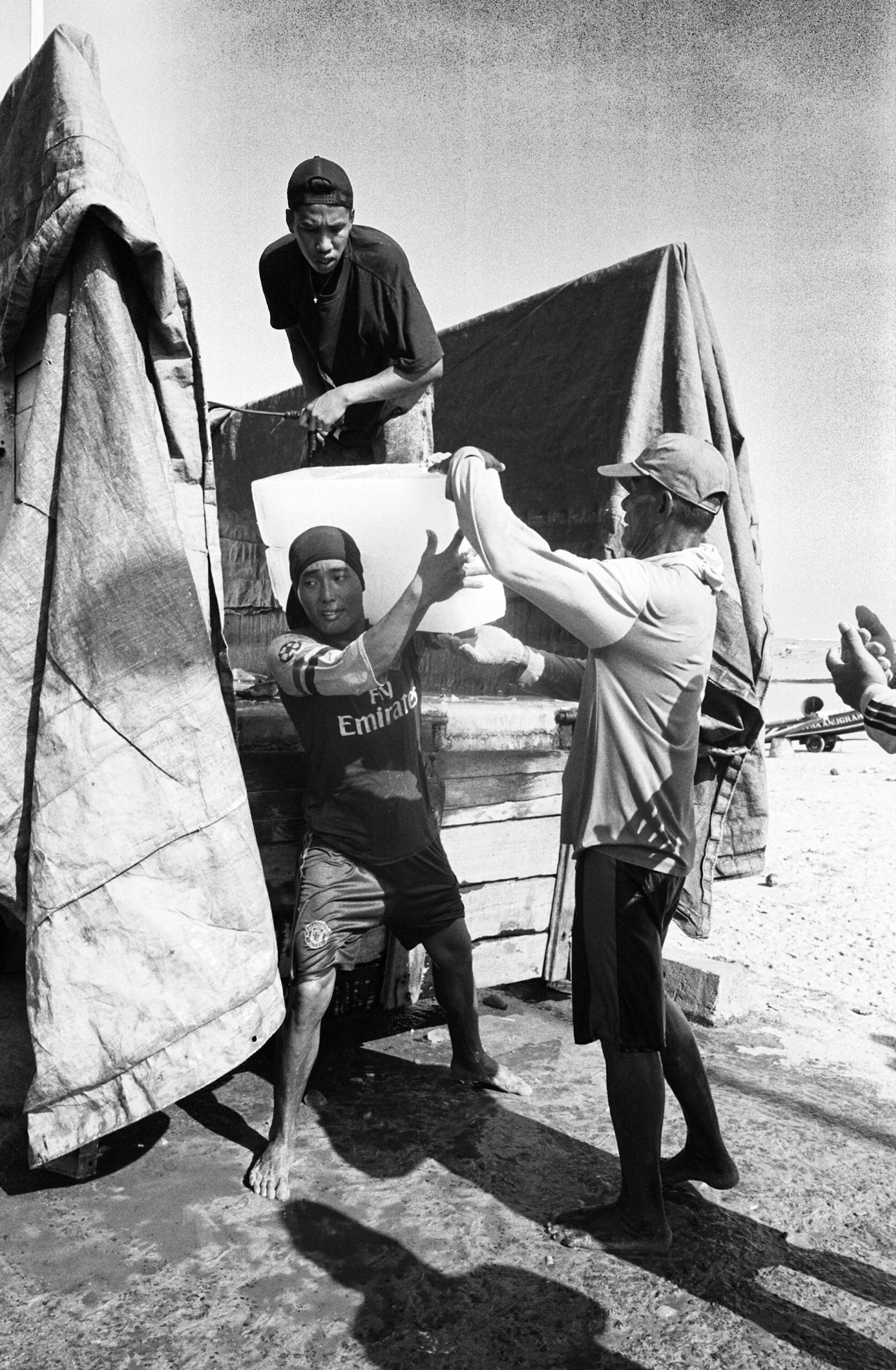

I first encountered Bali’s fishing communities years ago, while photographing dawn along the black-sand beaches near Amed and Kusamba. What struck me then—and still does today—is the quiet dignity of men returning from sea in fragile boats, faces carved by salt and patience. My lens often lingers on these moments: nets being mended, boats painted in bright colors fading under the sun, children learning to read the tides as naturally as others read screens.

Photos taken during one of my trips to Bali in June 2022, with a Leica M10-R using a 21mm Elmarit and 35mm Summilux, and a Leica M7 paired with a 35mm Summilux on Kodak T-Max 400 film.