There are moments, while walking through Hanoi’s Old Quarter with my

LeicaM11 Monochrom in hand, when history feels close enough to touch. It hides in the cracked walls of yellow shophouses, in the smell of incense rising from doorways, in the soft rumble of scooters pushing through narrow alleys. The city does not whisper its past — it breathes it. And on some mornings, especially when I am shooting in black and white, I find myself thinking of Võ Thị Thắng.

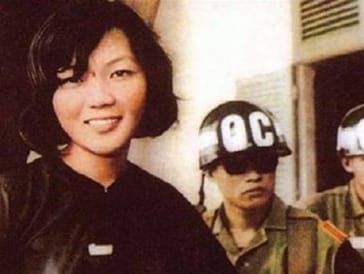

Her story is one of the most powerful in Vietnam’s long struggle for independence. Born in 1945 in a farming family outside Saigon, she joined the National Liberation Front as a young woman and quickly became known for her determination. Arrested in 1968 during the

Tet Offensive, she was sentenced by a South Vietnamese military court to twenty years in prison. It was meant to break her spirit. Instead, she answered with a smile.

There is a

photograph— iconic, almost mythological now — where Võ Thị Thắng stands before her judges, defiant and serene, smiling as she hears her sentence. The photo was taken by a Japanese reporter, and I was not able to find his name for an appropriate credit. That smile crossed borders, became a symbol, and told the world that courage can be louder than weapons. She later spent years at the infamous Chí Hòa prison, surviving solitary confinement and harsh conditions until her release in 1974, just before the fall of Saigon. After reunification, she held several governmental roles, always remembered for that calm, fearless expression that seemed to belong to a different dimension of resolve.

When I walk through Hanoi with that image in mind, something shifts. The Old Quarter, with its centuries-old textures and unanswered questions, becomes a place where resilience has been layered onto the city like lacquer on a wooden box. My black-and-white photographs try to

echothat feeling — the contrast between fragility and strength, the tightness of streets that somehow still open into light.

In the alleys around Hàng Bạc and Hàng Buồm, morning vendors set up their stalls while elders sit on low stools

sipping coffee, watching life unfold with the patience of those who have seen entire eras change around them. Faces appear framed by doorways, half in shadow, half in light — and I think again of that smile. Not the smile of joy, but of clarity. A refusal to be diminished.

Vietnam’s history is full of figures who shaped the country through grit and sacrifice, yet Võ Thị Thắng stands out because her defiance was expressed in such a human, universal gesture. A smile is not ideological. It is personal. It is intimate. And that is why it resonates so strongly when I look at my own images from Hanoi: a woman carrying fruit on a bamboo yoke; a child playing beneath weathered French balconies; an old man repairing shoes in a lane that hasn’t changed for decades. They all carry something of that spirit — unbroken, composed, forward-looking.

Photography, especially in monochrome, is a way to stop time and listen.

Last year I spent several weeks in Hanoi and northern Viet Nam, capturing social life with my Leica M11 Monochrome and a 18mm lens.